Antony Westwood: reflections on Harry Seidler

I first met Harry Seidler in 1996, the year I graduated from university. I had spent many hours after the completion of my studies walking around the Sydney CBD looking at buildings to glean some direction. Grosvenor Place and the Capita Centre stood out as rigorous, visually exciting and innovative buildings. So in February 1996, with my heart in my throat, I walked into the office of Harry Seidler & Associates and simply asked for a job. I was told there were no positions available. After some negotiation, I managed to secure a few weeks work experience, starting on the following Monday.

That particular Monday was one of the great days of my life. Harry approached my desk (and I can see him now, in the grey dust coat, wiry hair and bow tie) and demanded,‘What are your aims here?’ I proceeded to tell him of my admiration for his work and that I would be prepared to work for him without pay. I was to find out later that this struck a chord with Harry, who had used this very strategy as a graduate architect to enter Marcel Breuer’s office.‘You strike me as an enthusiastic and willing young man,’ he announced, ‘we’ll look after you’.

So began nine years of inspiration. I was to receive Harry’s tutelage in its full force, and I was always given the sense of being part of something extraordinary. From the very beginning Harry welcomed me into his close-knit and devoted team. Despite his driven and demanding exterior, I was struck by Harry’s loyalty and his sensitivity towards each of the individual team members. ‘This person holds the office together,’ he would say or, ‘there is something special about her’. Even better, ‘Learn everything you can from that person. He’s a genius!’ Everyone in the office talked about the ‘arm-squeeze’, where Harry gripped the upper arm of a team member, tightly, just above the elbow. For Harry, this was his way of expressing approval and affection.

I spent many hours with Harry travelling back and forth from one of our projects in the southern highlands of NSW. Harry spoke at length about the lessons that he received from Gropius, Breuer and Neimeyer; and of his meetings with Le Corbusier, Aalto and Utzon. It was thrilling to be in the company of someone who had associations with the great architects of the twentieth century.

Harry also spoke at length about the teachings and artwork of Josef Albers. Albers’ folio of colour plates entitled Artikulation became the textbook which Harry taught me about visual phenomena, or ‘what turns the eye on’, as Harry put it. I remember with great fondness the day that I was introduced to an Aubusson tapestry by Albers, from the ‘Homage to the Square’ series. I saw for the first time how the seemingly statically defined squares became unstable and dissolved into a field of fluctuating, pulsating colour. ‘Yes!’ Harry exclaimed (as he squeezed my arm) ‘the effect of tensional opposites on the apparatus of the eye …’

Not only was Harry a great architect, he was also an incredibly cultured man. Harry introduced me to Bach’s ‘St Matthew’s Passion’. Harry’s admiration for Bach’s music was based on his systematic manipulation of musical elements which suggested a spatial complexity and had clear associations with architecture. Later we studied the formal and visual aspects of one of the fugues from ‘The Well Tempered Clavier’. Harry had a well-thumbed copy of the music marked up with his own wiry handwriting. ‘I wish I had more time to play the piano,’ he said, a little wistfully.

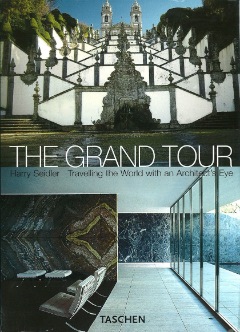

Harry could also draw a conceptual plan of every major city in the world. When any member of the team was about to travel abroad, he would enthusiastically sketch such plans, indicating the sites to be visited and photographed. His many slide shows of his own extensive travels where erudite lectures on architecture, urbanism and history. His travels are well documented in his book The Grand Tour, which reveals his appreciation and understanding of architecture throughout the history of civilisation. It is also a tender dedication to Penelope and his brother Marcel.

Harry could also draw a conceptual plan of every major city in the world. When any member of the team was about to travel abroad, he would enthusiastically sketch such plans, indicating the sites to be visited and photographed. His many slide shows of his own extensive travels where erudite lectures on architecture, urbanism and history. His travels are well documented in his book The Grand Tour, which reveals his appreciation and understanding of architecture throughout the history of civilisation. It is also a tender dedication to Penelope and his brother Marcel.

So long Harry. I will always remember you as a great architect, mentor and friend.

Antony Westwood